The statues and prints featured here are samples of Miltoniana available for purchase by aficionados of Milton and the poet’s Romantic heirs who championed his masterpiece, Paradise Lost.

Statuary

Prints

STATUARY

Ricardo Bellver’s El Ángel Caído (The Fallen Angel, 1877) — bonded natural marble statue

(Design Toscano)

A miniature replica of Spanish sculptor Ricardo Bellver’s El Ángel Caído, perhaps the quintessential Romantic vision of the Miltonic Lucifer. Sculpted in Rome in 1877, and based upon two passages from Paradise Lost’s grand introduction of the Hell-doomed and Heaven-defiant arch-rebel (I.36–38, 56–58), Bellver’s Fallen Angel focuses attention on the ruined archangel in Romantic fashion, his catastrophic fall from the celestial regions portrayed as more heroic than horrific. The Fallen Angel’s depiction of the Miltonic Lucifer in all his damned, defiant magnificence won Bellver First Medal in Spain’s National Exhibition of Fine Arts, held in Madrid in 1878, and since 1885 The Fallen Angel has resided in Madrid’s majestic Retiro Park, resting atop a towering pedestal in the midst of the Plaza del Ángel Caído. Design Toscano’s glittering Fallen Angel is a splendid small-scale replica of Bellver’s award-winning masterpiece.

A miniature replica of Spanish sculptor Ricardo Bellver’s El Ángel Caído, perhaps the quintessential Romantic vision of the Miltonic Lucifer. Sculpted in Rome in 1877, and based upon two passages from Paradise Lost’s grand introduction of the Hell-doomed and Heaven-defiant arch-rebel (I.36–38, 56–58), Bellver’s Fallen Angel focuses attention on the ruined archangel in Romantic fashion, his catastrophic fall from the celestial regions portrayed as more heroic than horrific. The Fallen Angel’s depiction of the Miltonic Lucifer in all his damned, defiant magnificence won Bellver First Medal in Spain’s National Exhibition of Fine Arts, held in Madrid in 1878, and since 1885 The Fallen Angel has resided in Madrid’s majestic Retiro Park, resting atop a towering pedestal in the midst of the Plaza del Ángel Caído. Design Toscano’s glittering Fallen Angel is a splendid small-scale replica of Bellver’s award-winning masterpiece.

Ricardo Bellver’s El Ángel Caído (The Fallen Angel, 1877) — bronze statue

(Veronese)

A miniature replica of Spanish sculptor Ricardo Bellver’s El Ángel Caído, perhaps the quintessential Romantic vision of the Miltonic Lucifer. The Fallen Angel was sculpted in Rome in 1877, and in the following year was featured in Spain’s National Exhibition of Fine Arts, held in Madrid, winning Bellver First Medal. In 1878, The Fallen Angel was also cast in bronze for the third Paris World’s Fair, and now resides within Madrid’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, Bellver’s alma mater. Veronese’s Fallen Angel is a magnificent small-scale replica of the bronze cast of Bellver’s masterpiece.

A miniature replica of Spanish sculptor Ricardo Bellver’s El Ángel Caído, perhaps the quintessential Romantic vision of the Miltonic Lucifer. The Fallen Angel was sculpted in Rome in 1877, and in the following year was featured in Spain’s National Exhibition of Fine Arts, held in Madrid, winning Bellver First Medal. In 1878, The Fallen Angel was also cast in bronze for the third Paris World’s Fair, and now resides within Madrid’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, Bellver’s alma mater. Veronese’s Fallen Angel is a magnificent small-scale replica of the bronze cast of Bellver’s masterpiece.

Lucifer Banished Angel — bronze statue

(Veronese)

This unique statue is not a modern-day example of Milton sculpture per se, but its depiction of Lucifer is unmistakably Miltonic, firmly in the tradition of Romantic renditions of Paradise Lost’s Prince of Darkness. Its long-haired Lucifer, clothed in quasi-classical garb—cuirass, skirt, sandals, greaves, and vambraces—sits atop a chunk of rock with his legs crossed, one hand gripping a long sword at his side, the other hand cradling his youthfully fair face, which reflects deep contemplation. Despite the title of the work, it remains unclear whether this rebel angel, enclosed by his own massive feathery wings, is portrayed after or before his fall from Heaven. While Paradise Lost itself notoriously blurs those two states—Milton emphasizing that the fallen archangel’s form is exceedingly angelic still, retaining a considerable degree of its “Original brightness,” this sublime Satan in fact appearing no less than “Arch-Angel ruin’d,” his “excess / Of Glory” merely “obscur’d” (I.592–94)—the Lucifer Banished Angel statue seems more a prelapsarian moment, perhaps when the erstwhile angel of light contemplates hatching his heavenly revolt—in Paradise Lost, the very moment that produces the birth of Sin from the celestial conspirator Satan’s own head (see PL II.749–58). Ambiguity aside, this Veronese Lucifer is an excellent modern-day incarnation of the rebel angel descended from the Miltonic-Romantic tradition.

This unique statue is not a modern-day example of Milton sculpture per se, but its depiction of Lucifer is unmistakably Miltonic, firmly in the tradition of Romantic renditions of Paradise Lost’s Prince of Darkness. Its long-haired Lucifer, clothed in quasi-classical garb—cuirass, skirt, sandals, greaves, and vambraces—sits atop a chunk of rock with his legs crossed, one hand gripping a long sword at his side, the other hand cradling his youthfully fair face, which reflects deep contemplation. Despite the title of the work, it remains unclear whether this rebel angel, enclosed by his own massive feathery wings, is portrayed after or before his fall from Heaven. While Paradise Lost itself notoriously blurs those two states—Milton emphasizing that the fallen archangel’s form is exceedingly angelic still, retaining a considerable degree of its “Original brightness,” this sublime Satan in fact appearing no less than “Arch-Angel ruin’d,” his “excess / Of Glory” merely “obscur’d” (I.592–94)—the Lucifer Banished Angel statue seems more a prelapsarian moment, perhaps when the erstwhile angel of light contemplates hatching his heavenly revolt—in Paradise Lost, the very moment that produces the birth of Sin from the celestial conspirator Satan’s own head (see PL II.749–58). Ambiguity aside, this Veronese Lucifer is an excellent modern-day incarnation of the rebel angel descended from the Miltonic-Romantic tradition.

PRINTS

Sir Thomas Lawrence’s Satan Summoning his Legions (1796–97) — print/canvas

(Royal Academy of Arts)

Satan Summoning his Legions—which made its debut at the Royal Academy of Arts’ annual exhibition of 1797, and is now featured in the RA’s new Collection Gallery—was the preeminent portraitist of Romanticism Thomas Lawrence’s daring early venture into history painting. The mammoth canvas, which towers at fourteen feet tall, depicts the moment from the first Book of Paradise Lost when Milton’s great “Apostate Angel” (I.125) rouses his fellow fallen angels from Hell’s burning lake with a thundering speech that culminates in the famous peroration, “Awake, arise, or be for ever fall’n” (I.330)—the line the young Shelley would later co-opt for the dramatic conclusion to his fiery Declaration of Rights (1812). While Satan Summoning his Legions was not particularly well received in 1797 (the pseudonymous satirist Pasquin famously dismissed it as “convey[ing] the idea of a mad German sugar-baker dancing in a conflagration of his own treacle”), and while Lawrence’s fellow Academician Henry Fuseli accused the young artist of copying from him (“it was from your person, not from your paintings,” Lawrence retorted, presumably to placate the Lucifer-like pride of the “Painter in Ordinary to the Devil” Fuseli), Lawrence to the end of his life believed his Satan to be his very best work. Considering Milton’s emphasis in Paradise Lost that the ruined archangel is not only dauntlessly defiant in Hell, with “Eyes / That sparkling blaz’d” beneath “Brows / Of dauntless courage, and considerate Pride” (I.193–94, 602–3), but that his fallen form is exceedingly angelic still, retaining a considerable degree of its “Original brightness” (I.592)—appearing in fact no less than “Arch-Angel ruin’d,” this sublime Satan’s “excess / Of Glory” merely “obscur’d” (I.593–94)—Lawrence’s Satan Summoning his Legions arguably pictures Milton’s majestic vision more successfully than any other painter or illustrator of Paradise Lost. The Royal Academy’s print/canvas of the renowned Romantic portraitist Lawrence’s monumental Miltonic painting captures perhaps the most idealized depiction of Paradise Lost’s princely arch-rebel, an image in the Miltonic-Romantic heritage rich in history.

Satan Summoning his Legions—which made its debut at the Royal Academy of Arts’ annual exhibition of 1797, and is now featured in the RA’s new Collection Gallery—was the preeminent portraitist of Romanticism Thomas Lawrence’s daring early venture into history painting. The mammoth canvas, which towers at fourteen feet tall, depicts the moment from the first Book of Paradise Lost when Milton’s great “Apostate Angel” (I.125) rouses his fellow fallen angels from Hell’s burning lake with a thundering speech that culminates in the famous peroration, “Awake, arise, or be for ever fall’n” (I.330)—the line the young Shelley would later co-opt for the dramatic conclusion to his fiery Declaration of Rights (1812). While Satan Summoning his Legions was not particularly well received in 1797 (the pseudonymous satirist Pasquin famously dismissed it as “convey[ing] the idea of a mad German sugar-baker dancing in a conflagration of his own treacle”), and while Lawrence’s fellow Academician Henry Fuseli accused the young artist of copying from him (“it was from your person, not from your paintings,” Lawrence retorted, presumably to placate the Lucifer-like pride of the “Painter in Ordinary to the Devil” Fuseli), Lawrence to the end of his life believed his Satan to be his very best work. Considering Milton’s emphasis in Paradise Lost that the ruined archangel is not only dauntlessly defiant in Hell, with “Eyes / That sparkling blaz’d” beneath “Brows / Of dauntless courage, and considerate Pride” (I.193–94, 602–3), but that his fallen form is exceedingly angelic still, retaining a considerable degree of its “Original brightness” (I.592)—appearing in fact no less than “Arch-Angel ruin’d,” this sublime Satan’s “excess / Of Glory” merely “obscur’d” (I.593–94)—Lawrence’s Satan Summoning his Legions arguably pictures Milton’s majestic vision more successfully than any other painter or illustrator of Paradise Lost. The Royal Academy’s print/canvas of the renowned Romantic portraitist Lawrence’s monumental Miltonic painting captures perhaps the most idealized depiction of Paradise Lost’s princely arch-rebel, an image in the Miltonic-Romantic heritage rich in history.

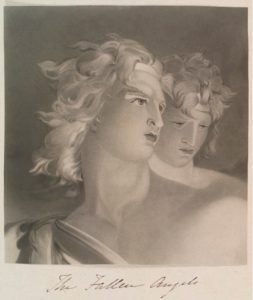

Sir Thomas Lawrence’s The Fallen Angels (1796–97), engraved by William Say — print

(National Portrait Gallery)

The Fallen Angels is William Say’s engraving after Sir Thomas Lawrence’s Satan as the Fallen Angel, a two-thirds profile sketch of Milton’s Satan, executed around the same time the artist was working on his monumental Miltonic canvas of Satan Summoning his Legions (1796–97). Lawrence had first sketched portraits of Paradise Lost’s characters as early as 1785, and his sketch of Milton’s Satan, the artist noted at the time, was rendered not with “horror” but “more Majesty & Bearing”; Lawrence later captured the same devilish dignity with Satan as the Fallen Angel, as its windswept subject rather resembles the Apollo Belvedere, both in facial features and positioning—with nape-long, windswept hair, the fallen angel staring off into the infernal distance with glistening eyes, his Apollonian countenance reflecting greater valor than that of Beëlzebub, who stands behind him. Both here and in the canvas, Lawrence captures better than any other Romantic artist—or any other Milton illustrator, generally speaking—the dynamic between Satan and his second-in-command: as in Paradise Lost, Lawrence’s Beëlzebub is attractive and powerful like Satan, yet not as attractive, not as powerful as Satan.

The Fallen Angels is William Say’s engraving after Sir Thomas Lawrence’s Satan as the Fallen Angel, a two-thirds profile sketch of Milton’s Satan, executed around the same time the artist was working on his monumental Miltonic canvas of Satan Summoning his Legions (1796–97). Lawrence had first sketched portraits of Paradise Lost’s characters as early as 1785, and his sketch of Milton’s Satan, the artist noted at the time, was rendered not with “horror” but “more Majesty & Bearing”; Lawrence later captured the same devilish dignity with Satan as the Fallen Angel, as its windswept subject rather resembles the Apollo Belvedere, both in facial features and positioning—with nape-long, windswept hair, the fallen angel staring off into the infernal distance with glistening eyes, his Apollonian countenance reflecting greater valor than that of Beëlzebub, who stands behind him. Both here and in the canvas, Lawrence captures better than any other Romantic artist—or any other Milton illustrator, generally speaking—the dynamic between Satan and his second-in-command: as in Paradise Lost, Lawrence’s Beëlzebub is attractive and powerful like Satan, yet not as attractive, not as powerful as Satan.

Henry Fuseli’s Roman sketch of Satan and Death Separated by Sin (1776) — print/canvas

(Ashmolean Museum)

The Swiss-born painter and draftsman Henry Fuseli was the British Romantic art world’s most ardent Milton devotee. Fuseli was particularly fond of picturing Milton’s Satan, so much so in fact that he earned the Satanic sobriquet “Painter in Ordinary to the Devil,” to which the artist is said to have responded warmly, “Aye! he has sat to me many times.” The first time the Miltonic Satan sat for Fuseli, as it were, was in Rome in October of 1776, in this sketch of Satan and Death Separated by Sin, a scene from Paradise Lost the painter would repeatedly return to throughout life, not least in his Milton Gallery (1799, 1800), the great and ill-fated Miltonic endeavor of his career. Fuseli, who has sometimes been referred to as “the first of the Romantics,” was Romanticism’s most prolific illustrator of Milton, and Satan and Death Separated by Sin not only marks the first of Fuseli’s scores of Miltonic pieces, but also perhaps the first sighting of the Romantic Satan: beautifully Apollonian in appearance and heroically godlike in form, fashioned with angelic wings and proud bearing, and dauntlessly defiant in the face of terrifying adversity. The Ashmolean’s print/canvas of Satan and Death Separated by Sin captures not only a seminal Fuseli sketch but a defining moment in the history of Romantic Milton illustration.

The Swiss-born painter and draftsman Henry Fuseli was the British Romantic art world’s most ardent Milton devotee. Fuseli was particularly fond of picturing Milton’s Satan, so much so in fact that he earned the Satanic sobriquet “Painter in Ordinary to the Devil,” to which the artist is said to have responded warmly, “Aye! he has sat to me many times.” The first time the Miltonic Satan sat for Fuseli, as it were, was in Rome in October of 1776, in this sketch of Satan and Death Separated by Sin, a scene from Paradise Lost the painter would repeatedly return to throughout life, not least in his Milton Gallery (1799, 1800), the great and ill-fated Miltonic endeavor of his career. Fuseli, who has sometimes been referred to as “the first of the Romantics,” was Romanticism’s most prolific illustrator of Milton, and Satan and Death Separated by Sin not only marks the first of Fuseli’s scores of Miltonic pieces, but also perhaps the first sighting of the Romantic Satan: beautifully Apollonian in appearance and heroically godlike in form, fashioned with angelic wings and proud bearing, and dauntlessly defiant in the face of terrifying adversity. The Ashmolean’s print/canvas of Satan and Death Separated by Sin captures not only a seminal Fuseli sketch but a defining moment in the history of Romantic Milton illustration.

Mike Mahle’s Paradise Lost cover (Rock Paper Books edition) — print

(Rock Paper Books)

Rock Paper Books illustrator Mike Mahle offers up an interesting modern-day take on the Miltonic Satan for the cover of the Rock Paper Classics edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost, which is available as a print. A bulky Satan with streaming ebony locks and pitch-black bat-wings lies atop a rocky precipice in a violently reddish Hell, his head downcast in defeat, which is signified by his broken blade and cracked shield beside him, as well as his fellow fallen angels plummeting headlong into perdition far behind. Mahle does a fine job of capturing Milton’s vision of Satan’s “faded splendor wan” (PL IV.870), and this modern fantasy art print makes for a notable nod to Romanticism’s Miltonic artwork.

Rock Paper Books illustrator Mike Mahle offers up an interesting modern-day take on the Miltonic Satan for the cover of the Rock Paper Classics edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost, which is available as a print. A bulky Satan with streaming ebony locks and pitch-black bat-wings lies atop a rocky precipice in a violently reddish Hell, his head downcast in defeat, which is signified by his broken blade and cracked shield beside him, as well as his fellow fallen angels plummeting headlong into perdition far behind. Mahle does a fine job of capturing Milton’s vision of Satan’s “faded splendor wan” (PL IV.870), and this modern fantasy art print makes for a notable nod to Romanticism’s Miltonic artwork.

Ruth Thompson’s War in Heaven — print/canvas

A unique interpretation of the apocalyptic War in Heaven by fantasy artist Ruth Thompson for The Book of Angels (2006), which depicts the heavenly Lucifer as the Light-Bearer—as his native name denotes—with his angelic opponents (counterclockwise from bottom) Gabriel, Michael, Uriel, and Raphael charging in flight toward the resplendent rebel angel. While not an illustration of Milton’s Paradise Lost per se, this War in Heaven’s angelic cast is decidedly Miltonic, the “Sun-bright” (PL VI.100) Satan especially so. Thompson’s War in Heaven print/canvas makes for an excellent example of the Miltonic-Romantic tradition’s continued influence on fantastical artwork in our own day and age.

A unique interpretation of the apocalyptic War in Heaven by fantasy artist Ruth Thompson for The Book of Angels (2006), which depicts the heavenly Lucifer as the Light-Bearer—as his native name denotes—with his angelic opponents (counterclockwise from bottom) Gabriel, Michael, Uriel, and Raphael charging in flight toward the resplendent rebel angel. While not an illustration of Milton’s Paradise Lost per se, this War in Heaven’s angelic cast is decidedly Miltonic, the “Sun-bright” (PL VI.100) Satan especially so. Thompson’s War in Heaven print/canvas makes for an excellent example of the Miltonic-Romantic tradition’s continued influence on fantastical artwork in our own day and age.